Gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) gut passage can alter seed germinability

15 Aug 2018

In addition to dispersal, ingestion of seeds by animal guts may also alter the number of seed germinating and/or the time to germination (collectively referred to as germinability).

In this experiment, I examined whether the germinability of seeds passing through gopher tortoises differs from seeds that are uningested, and if seed germinability is affected by the presence of scat. Changes in seed germinability following ingestion may result from three mechanisms: 1) mechanical or chemical alteration in response to gut passage; 2) Presence of scat surrounding the seed acting as a fertilizer; and/or 3) separation of seeds from surrounding plant tissues such as fleshy fruit.

Not all fruit is fleshy and adapted to dispersal by animals. Grass, oak trees (acorns), and 98% of other plants all have seeds encapsulated in fruit, we just don’t typically think of them as such in our day to day lives. So tortoises are actively seeking out fleshy fruits like cacti and Physalis, but they are also ingesting seeds intented for wind dispersal and other non-animal dispersal syndromes. Take a look at the photo below.

See those white flowers? Those will eventually become pollinated and set seed. Some may already have on those plants, we just can’t see them. Tortoises really like that plant, and in ingesting the leaves will also be ingesting seeds because they are small and inconspicuous.

Using some plant species from the tortoise exclosure experiment, I hypothesized that seeds from fleshy fruits, which have evolved to be eaten and dispersed by animals, will have higher germination percentages and less time to germination following gut passage. Seeds from dry fruits, which may be wind dispersed, will have lower germination percentages following gut passage but unaltered time to germination. The presence of scat was hypothesized to increase germination percentages and decrease time to germination in all species of seeds.

Seeds were fed to tortoises and collected out the other end by sifting through scat. A 2 x 2 factorial design was used to compare the germinability of control vs. gut-passed seeds and presence or absence of scat to determine if any differences observed from gut passage were from physiological changes to seeds as a result of ingestion or a fertilizer effect, respectively. Seeds were planted in germination trays filled with natural field-collected sandy substrate. Half of the gut-passed seeds were added to the germination trays as described above, the other half were added to cells that received a thin layer of blended and microwave-sterilized scat. An equal number of control seeds were added to each scat treatment in a similar manner. All seeds were covered lightly with a thin layer of media and then trays were covered. Emergence day was recorded for each seed.

Differences in passage time were tested between fleshy and dry seeds using generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMMs) with a Gamma distribution, with passage time as a fixed effect and tortoise identity as a random effect. We tested percent of seeds germinating and time to germination (number of days) per each treatment per tortoise (that is, averaged across seven tortoises) using GLMMs with scat presence and gut passage as fixed effects and tortoise identity as a random effect. A binomial distribution was used for percent of seeds germination and a Gamma distribution for time to germination.

Here’s what was found:

Gut passage effects

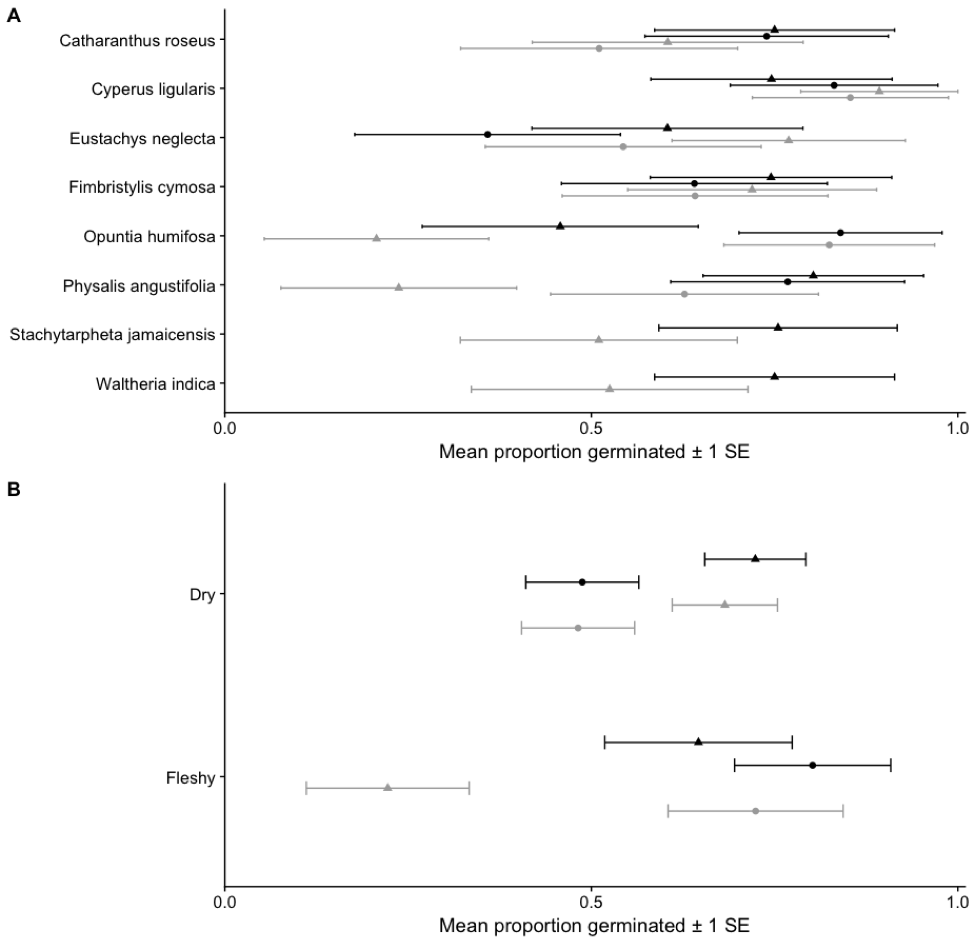

Mean proportion of seeds germinated A) by species and B) pooled across dry and fleshy fruits for seeds that have passed through the gut (●) and those that have not (▲) and planted with scat (black) and without (gray). Values are averaged across the seven tortoises and associated controls.

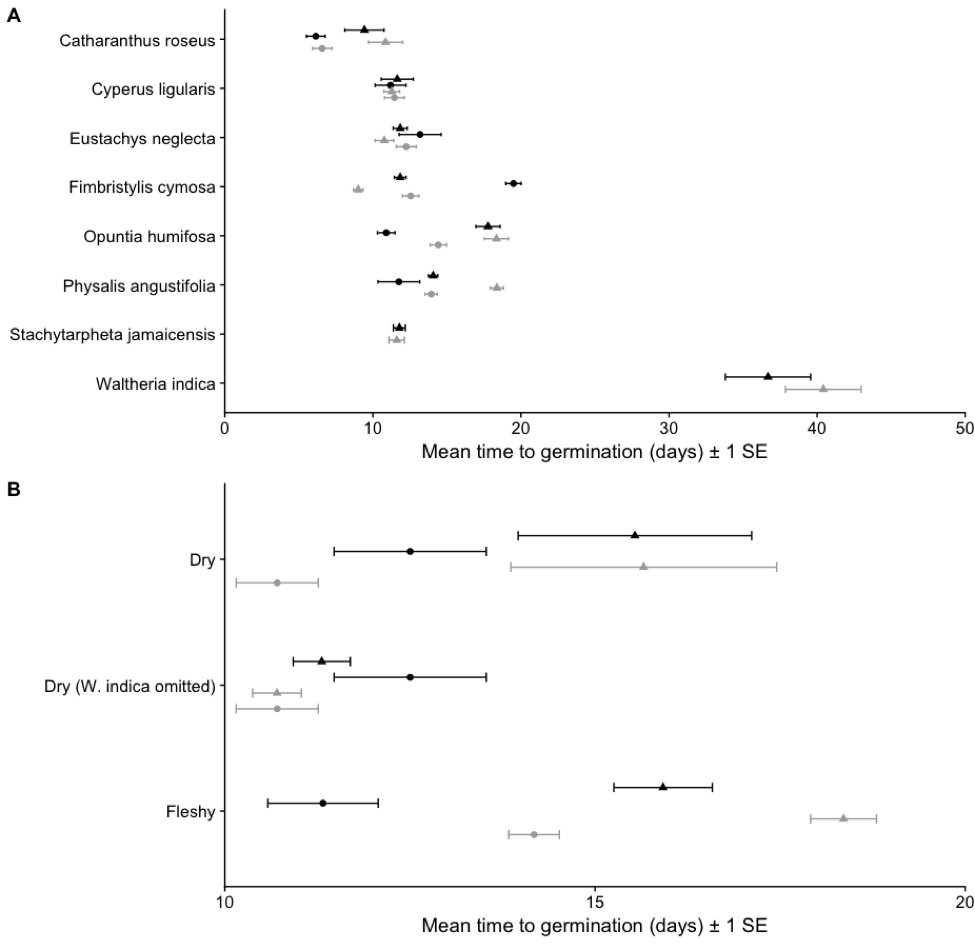

Mean time to seed germination a) by species and b) pooled across dry and fleshy fruits for seeds that have passed through the gut (●) and those that have not (▲) and planted with scat (black) and without (gray). Values are averaged across the seven tortoises and associated controls.

Seeds from the two fleshy-fruited species, germinated in significantly greater proportions (Opuntia humifosa X2 = 48.982, df = 1, p < 0.0001; Physalis angustifolia X2 = 7.258, df = 1, p = 0.0070) and faster (O. humifosa X2 = 92.064, df = 1, p < 0.0001; P. angustifolia X2 = 18.356, df = 1, p < 0.0001) after gut passage than seeds that did not pass through the gut. The five native dry-fruited plants (Catharanthus roseus is introduced) were either not significantly affected, or had lowered germination percentages and/or increased time to germination following gut passage. Two species, Stachytarpheta jamaicensis and Waltheria indica, failed to germinate entirely after gut passage. In the introduced C. roseus, germination percentage following gut passage was not significantly altered (X2 = 0.596, df = 1, p = 0.4399), but time to germination decreased (X2 = 18.410, df = 1, p < 0.0001). Pooling species into fleshy and dry fruits reveals overall that the two fleshy fruits have increased germination percentage after gut passage (X2 = 60.784, df = 1, p < 0.0001), and lowered time to germination (X2 = 10.805, df = 1, p = 0.001). Dry seeds that haved passed through the gut have inhibited germination percentages (X2 = 60.784, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and time to germination (X2 = 10.805, df = 1,p = 0.0010).. This delay in germination time is skewed by W. indica. Comparing germination time in ingested and control dry seeds excluding W. indica indicates that gut passage overall had no effect (X2 = 0.989, df = 1, p = 0.3197).

Scat effects

Seeds from the two fleshy-fruited species, germinated in greater proportions (O. humifosa X2 = 5.432, df = 1, p = 0.197; P. angustifolia X2 = 28.751, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and faster (O. humifosa X2 = 13.105, df = 1, p = 0.0002; P. angustifolia X2 = 16.990, df = 1, p < 0.0001) with scat addition than seeds in the control substrate. The five native dry-fruited plants were either not significantly affected by scat addition, or had lowered germination percentages and/or increased time to germination. Germination percentage significantly increased in C. roseus following scat addition (X2 = 6.977, df = 1, p = 0.0082) but time to germination was not affected (X2 = 1.109, df = 1, p = 0.9064). Grouped by fruit type, fleshy fruits germinate in greater percentages under scat exposure (X2 = 32. 368, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and dry fruits are unaffected (X2 = 07585, df = 1, p = 0.3838). Time to germination in pool fleshy fruits is lowered (X2 = 22.360, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and unaffected in dry fruits (X2 = 0.296, df = 1, p = 0.5862). Excluding W. indica does not lead to a different outcome (X2 = 3.561, df = 1, p = 0.0591).

Interactions

There were significant interactions between gut passage and the presence of scat for only two plant species, both of which were fleshy-fruited. Gut passage reduced the time to germination in O. humifosa, the addition of scat further reduced the time to germination (X2 = 17.628, df = 1, p < 0.0001). Second, P. angustifolia proportion germinated was lower in the control without the addition of scat (X2 = 10.109, df = 1, p = 0.0014).

Full code available on my github account.